My wife and I recently rented some offices above the Sikh temple community hall in our neighborhood. Pulling back the carpet we discovered a hidden treasure– oak hardwood floors. Unfortunately they were pretty trashed. Around the edges of the room there was this residue of white spray paint. I stood back a moment and realized that at some point in the 1980’s they’d painted these walls and knowing they would carpet the floors, gave no concern to where the paint fell. The rest of the floors looked tired from thirty plus years under carpet, stained by countless spills and roof leaks. It boggles my mind that at some point in the 70’s and into the 80’s people preferred carpet to shiny, hardwood floors.

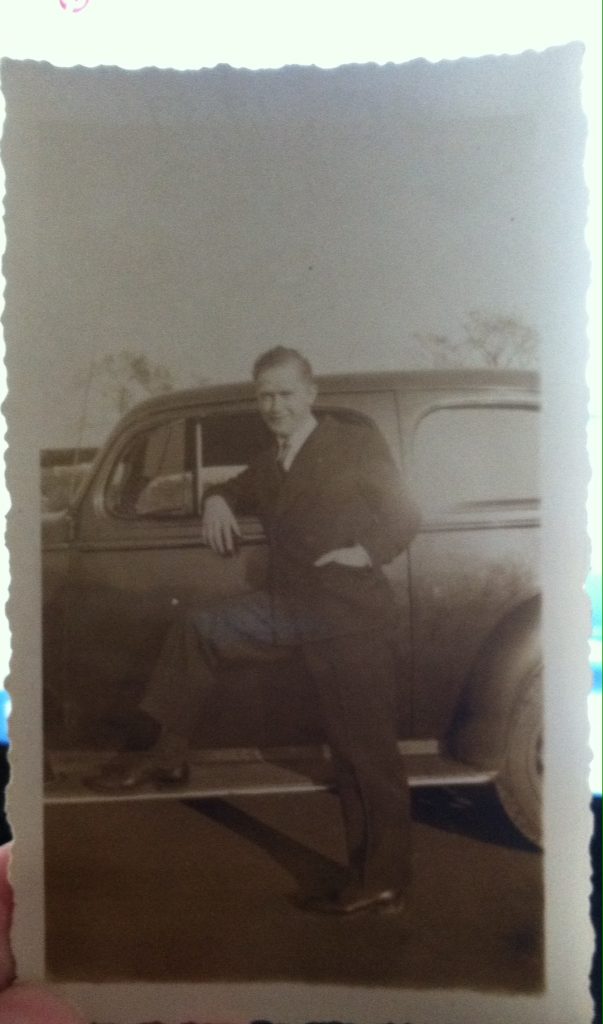

I thought of my grandfather Joe Kalman. That was his profession– he refinished hardwood floors, only back then he called himself a floor scraper. That’s what it was called. A floor scraper, simple and unassuming– just like Joseph Francis Kalman. I decided to refinish the floors myself and as I did so, a flood of fond memories came back.

I thought of my grandfather Joe Kalman. That was his profession– he refinished hardwood floors, only back then he called himself a floor scraper. That’s what it was called. A floor scraper, simple and unassuming– just like Joseph Francis Kalman. I decided to refinish the floors myself and as I did so, a flood of fond memories came back.

He wore thick denim work pants, blue-jeans. He called them “dungarees.” With that he wore work shirts that were a lighter blue, also made of denim. That’s where the term blue-collar came from. It was a uniform back then. He was the epitome of a blue-collar man, honest and hard working. I remember being glad to see him when he got home from work. He drove an old 1955 dark blue Chevy panel van which was affectionately known as The Truck. He would pull up in front of the Bronx apartment building on 188th Street in between Tiebout Avenue and Elm Place. Sometimes there wouldn’t be a free parking meter so he would wait, parked in front of the fire hydrant, waiting patiently for a spot. Sometimes he got lucky and found a spot right off. Sometimes he had to wait, sitting in the truck listening to the radio. It seemed like a big pain to me but he just treated it like one more thing he had to do.

Inside the truck was all his gear– rags and brushes and buckets with thick crusts of amber-like shellac. They looked like the drip from candles only golden with lac resin. He would cover up all that stuff with blankets, along with the large belt sander, which was far too heavy to steal. The orbital sander and other valuables he would carry up the five story walk-up tenement steps to the 4th floor apartment where all eleven of us lived, in a three-room, railroad style flat. That’s how it was done back then– extended family all in one place. Although he was my grandfather, I remember these details because for the first seven years of my life I lived in my Grandparent’s home. My mother was the oldest and I was the first grandchild. So everybody was there when I arrived– the whole family. It was heaven for a little kid. Five aunts and an uncle, two grandparents and a grand uncle all under one roof. That’s a lot of attention for the baby, the first grandchild and I soaked it all up, but the best part of it all was my grandfather, Joe. Not only was he very loving and I am sure very proud of having his first grand child, but he was also very strong. Not the kind of strong that will go chest to chest with someone and win by punches, but the kind of strong that uses wisdom and solid stance, forbearance and personal will to do the right thing by his family day after day. I remember being held by him, holding on to his strong bi-ceps, which were like carved stones, they were so solid. His blue shirt and pants were stained by hard work and he smelled a mixture of sour sweat, wood dust, stain, shellac and the petroleum smell of polyurethane. I would ask him to make a muscle and I would squeeze his bicep with my little hands and marvel at his strength. One time we were lying on one of the bunk beds in the front room as he called it. I was sitting on his chest and swinging my arms in some game we were playing and I accidentally hit his nose and it started to bleed. I immediately started crying. I felt so bad that I had hurt him. He just laughed it off and told me he was okay as he wiped the blood off on his sleeve. From my earliest, I remember him as a pillar of strength.

When he watched TV shows like Gunsmoke he’d grunt and yell as the punches were thrown as through he were right there in the fight with the actors. In fact, he was so into his programs that I started to wonder if TV was real life somewhere else and we were seeing it through that box. I remember thinking one day that they must have have found people who wanted to die and were willing to make that ultimate sacrifice on film for the sake of telling a great story. I was sure that’s how they were able to capture these fight scenes and shoot-outs. One night Muhammad Ali was fighting Joe Frasier and Grandpa walked around the apartment all night with a little ivory white transistor AM radio, listening to round after round with rapt attention. He was deep into his life. Those small pleasures he savored. Although it was a hard life, he didn’t complain or bare his soul like they do today in this culture of therapy and getting things off your chest. He was a man, the man of the house, and he handled his business without complaint.

There was a lot of yelling in that house. Years later as a writer, living in my Los Feliz, California apartment I would hear my next door neighbor, a 90 year old Romanian woman, yelling at her 46 year-old son and he at her. He would drive in from Vegas to visit her about once a month. And each time there would be yelling between the white-haired old lady and her round, dark-haired son. This day I’d had enough of listening to their screaming match. I went next door where they were going at it with the door opened, only a screen door between them and the whole building.

“Listen if you’re going to have a fight could you please at least close your door? I’m trying to work over here.” I said.

Their faces went blank, as though I had just accused them of betraying each other.

“We’re not fighting,” said the old woman, “This is just how we talk.”

I laughed and walked back to my place. I knew exactly what they meant. My whole family talked like that. There was a love there but it was covered in the tension that comes from poverty and living in such close quarters. And honestly the only thing holding it all together was Joe Kalman.

They had a lot of problems. Only back then people didn’t talk about those problems like they do today. They just dealt with it and took life’s punches and did their best to push back as necessary. I remember my grandfather and grandmother fighting a lot. They lived through World War II and again, they never complained about what they suffered. It was just life and it happened. But today we’d recognize some of their symptoms as what was called Battle Fatigue back then, and what they call PTSD today. I have a distinct memory of one day, when my Grandfather and Grandmother walked down the apartment steps hand in hand, to take a walk. It was a very rare display of affection between the two. The family stood and joked with about them having another child. I remember that moment very well because it resonates much more than many of the memories of fights and discord. That’s how love works. It trumps all else. They loved each other, because with all its imperfections they created life together– several lives, including my own. And in their own way, they loved those children and provided for them the best that they knew how.

For my mother and some of her siblings it was much more painful because they were closer to the pain of war that both my grandfather and grandmother carried. I on the other hand remember only showers of love from them both. I had the luxury of coming in later. Despite that love, there were the scars of war. I remember soaking up their stories, especially the things that adults let slip. As the story goes, my grandmother was engaged to a doctor during the war. He was Chinese and she Irish– which at that time was a bold move for a couple. Mixed relationships were not well accepted back then, even in the big city. He was killed when the hospital ship he was working on was sunk in the Pacific. As my mother described it to me, my Grandfather and Grandmother got married on the rebound. Another thing that my mother shared with me was that my Grandfather left the family once. When she was still the only child, he left because they weren’t getting along. But he came back and he told her why: He didn’t want his child growing up an orphan like he did. And that sums up his character above all else. Love is about sacrifice for another and he sacrificed his potential happiness in a tough marriage, for his daughter, my mother, above all else. As the other children came, as was inevitable for an Irish Hungarian Catholic family of that time, his character never changed. He worked and worked through good times and bad, highs and lows, to provide for his family.

My grandmother was often ill. In addition to being diabetic, she clearly suffered the mental demons which haunted her from the war. She was often on medication and spent a lot of time in bed. I forget how it came up, but I remember my grandfather telling me a story once. He was telling me how he’d worked all day on a job and came home to a house of hungry kids, a sick wife and no clean clothes for anyone. He fed the kids and after that he went into the bathroom and with the ribbed glass washboard and a bar of brown soap he scrubbed the clothes for the five children so they would have clean clothes for school in the morning. I could see the whole scene as he described it. Then he told me that he was so tired that he sat on the edge of the bed, rested his face in his hands and when he awoke, it was morning again and he had to turn right around and go back to work. Hauling the sander and cans of stain down the four flights and into the Chevy van, driving up to polish the hardwood floors of rich New York homeowners in Westchester and Scarsdale. I remember the impact that story had on me. At the time my heart felt like an abyss of emptiness as he told it. It was the saddest thing I’d ever heard. When I said how sad it was, he just laughed it off with his big smile, like it was no big deal. It was no big deal because he made it through and he’d lived to tell the story to his grandson. It was a victory. And that was how he was. He was a man and he lived like a man, for his family.

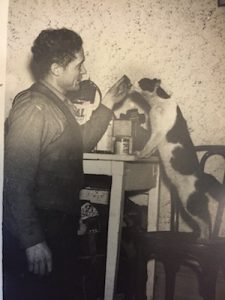

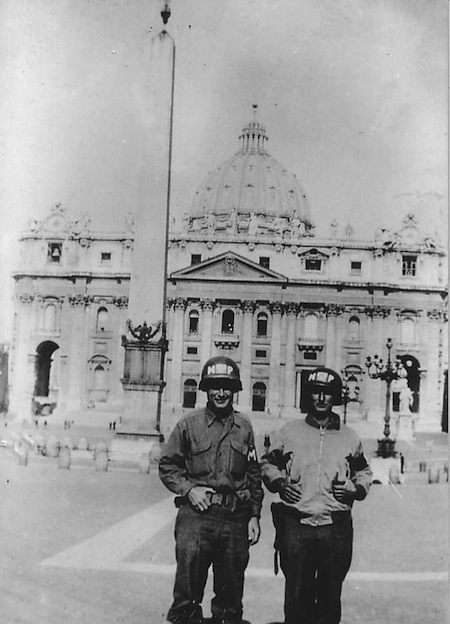

I asked him about the war a few times as a kid. He told me he was an MP and he was stationed in Italy. He’d tell me amusing stories about the war. I asked him a few times if he’d ever had to kill anyone and he’d either say “no,” flat out, or he’d redirect and recount something clever about a situation or a buddy. It was always positive. I can’t remember the specifics because I believe they were only half truths. Years later I was accepted to West Point and in my second year I had come down to visit him. We were sitting at the kitchen table in that same Bronx apartment. The kitchen walls had been painted so many times that they bubbled in spots. By this time the color was canary yellow. The walls looked tired, as he did with his wavy hair, now pure white. He wore the same blue work shirt as he always had and in fact, he was still going to work most days because he was such an artisan that he was very much still in demand. He was in his seventies now, and although he moved a little slower he was very clear, and still quite strong.

I asked him about the war a few times as a kid. He told me he was an MP and he was stationed in Italy. He’d tell me amusing stories about the war. I asked him a few times if he’d ever had to kill anyone and he’d either say “no,” flat out, or he’d redirect and recount something clever about a situation or a buddy. It was always positive. I can’t remember the specifics because I believe they were only half truths. Years later I was accepted to West Point and in my second year I had come down to visit him. We were sitting at the kitchen table in that same Bronx apartment. The kitchen walls had been painted so many times that they bubbled in spots. By this time the color was canary yellow. The walls looked tired, as he did with his wavy hair, now pure white. He wore the same blue work shirt as he always had and in fact, he was still going to work most days because he was such an artisan that he was very much still in demand. He was in his seventies now, and although he moved a little slower he was very clear, and still quite strong.

We got to talking about the military. I told him how we’d been out in the field training during the summer and how it had rained and we were shivering in a foxhole all night. One of the guys in my squad was prior-service so he had some experience. He told us to reach into our waterproof bags and just put on a dry t-shirt. It seemed stupid. We were wet anyway, what difference was a dry t-shirt going to make under the rest of the wet gear? “Just do it,” he said. So I did and I slept like a baby after that. My grandfather smiled as I told him all this. He told me how during the war it had been weeks, maybe even months that they had gone with out a shower or even clean uniforms and then one day he was finally able to take a shower and put on just one clean t-shirt and it was the best, deepest sleep he’d ever had. He started telling me more stories. How he’d met General Patton once. Patton was a 1915 graduate of West Point. Joe was standing guard outside the tent where General Patton was addressing his staff. He said he was scared, standing at attention outside the tent because old “Blood and Guts” Patton was screaming a litany of curses at whomever he was addressing and he’d never heard anybody curse like that in his whole life. At one point I asked him again, “Didja ever have to kill anybody?” Only now he didn’t redirect. He got a look in his eyes, a far off stare. He was silent for some time and when he spoke it was concise.

“It was dark. One night there was movement. And I shot at this thing.” He paused, as if thinking better of it and then he backed off it.

“I think… turned out it was a dog, or something.” He changed the subject.

I never pressed him on it but I always knew it was more than just a dog, and very likely that wasn’t the only incident.

All these memories of the man came back to me as I sanded that office floor with the same type of orbital sander he used. I rubbed stain into the open fresh smelling wood with an old rag and then later, sealed it with coat after coat of shellac. The textures and smells brought back a flood of The Bronx, the family and the Patriarch of 307 East 188th Street, Apartment 4E, the man who held it all together– Joe Kalman.

As I finish writing this, I realize that it is March 8th, Joe Kalman’s birthday. He would’ve been 100 years old today.

Wow..that is awesome.

Grandpa-Father and Hero!